Metro cares about transit walk sheds because more households accessible to transit by walking translates directly into more ridership.

We’ve been focusing a lot on transit walk sheds lately. We’ve shown that the size of a transit walk shed depends heavily on the roadway network and pedestrian infrastructure, and that these sizes vary dramatically by Metrorail station. We’ve also demonstrated that expanding the walkable area can make hundreds of households walkable to transit.

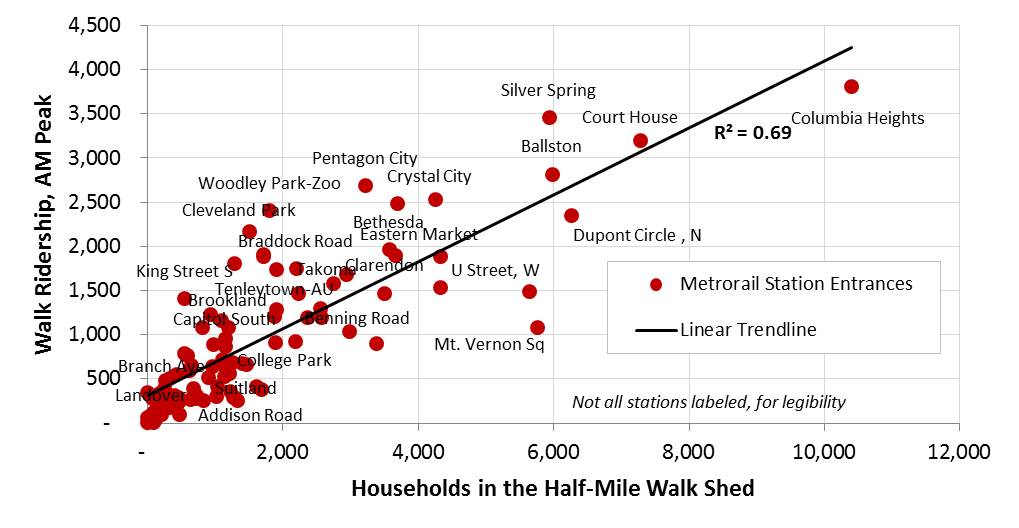

But why do we care so much about walk sheds? Because larger walk sheds mean more households in the walk shed, and that means ridership. For example, we’d be hard pressed to find many households in Landover’s small walk shed, so it’s no surprise that walk ridership at that station is low. On the other hand, thousands of households are within a reasonable walk to Takoma’s larger walk shed, and walk ridership there is much higher.

In other words, the more people can walk to transit, the more people do walk to transit – and data across Metrorail stations prove it:

|

| More households in the walkable area around a Metrorail station means higher ridership. |

The chart above shows that the number of households in a Metrorail station entrance’s walk shed is highly correlated with AM Peak walk ridership at that station. In fact, the number of households walkable to a Metrorail station alone explains nearly 70% of the variation in walk ridership across Metrorail stations.Click here to read the rest of this post.

The results and certainly the conclusions are similar to a short, more technical paper we wrote for the Reston Task Force and posted on this blog in 2011 entitled, "The Residential vs. Employment Balance in TOD Areas: Optimizing for Reduced Congestion and Environmental Damage." The two key graphics in that report show that residents of a Metro station area "walk shed" ("the half-mile circle") are much more likely to use Metro than people who work in that station area. They also show the converse: That people who work in a station area are much more prone to drive to that station area at any given distance from the station than are the people who live there.

Our report was based on a 2005 WMATA survey of Metrorail ridership. Since we are unaware of any more recent such surveys, we suspect the PlanItMetro article is a more fine-grained analysis of the same report. The results in both these reports is consistent with a significant body of research on the topic: Residents of a transit station area are much more likely to use transit than workers in the station area.

Nonetheless, the point received absolutely not attention by the developer-driven task force, which was intent on allowing massive office space development and little residential development, especially within the critical first 1/4 mile of the Metro station. This was especially true in the Town Center area. Even advocates for Metrorail on the task force, including its DCRA President chairman, did not grasp--or chose to ignore--the importance of nearby residential development to Metrorail ridership. The same was true to an even much greater extent in the Tysons Task Force.

In the end, the County planning staff modestly muted the jobs-to-residential ratio and density (total square footage of allowable developed space) in the final plan subsequently approved by the County Board in the face of traffic analyses that showed even more massive gridlock than we can expect under the approved plan. The final density, most notably in Reston Town Center, is less than proposed by the task force's Town Center Sub-committee, dominated by Boston Properties and its allies, and a better balance, that is, more residential, than the sub-committee proposed. Still, the County's analysis of the approved development plan shows that, when the planned development is completed, Restonians can expect five-minute or more traffic delays at each intersection along the key through streets (Reston Parkway, Wiehle) in the station area during peak traffic periods--even if all the planned street infrastructure is in place!

And none of this considers the much reduced--and declining--office space per worker now seen in office property leasing. Recent trends reported here several times in letters to Board Chairman Sharon Bulova (see here, here, here, and here) show that the office space per worker is being cut by half at least for a variety of reasons, meaning we can anticipate at least twice as many workers in the allowed plan office space than the plan envisions--and about twice as much traffic as has been assessed.

All of this belies the stated goal of Reston Master Plan re-make to take advantage of the arrival of Metrorail since little the task force did actually took advantage of the transit opportunities the arrival of Metrorail presents. Rather it was about increasing developer and landowner profit opportunities and especially the County's real estate property tax base. Unfortunately, the turn in the economy and the reduction of federal spending has shown all the growth assumptions prepared by developer-funded GMU's Center for Regional Analysis, including the developer controlled "2030 Group" lobbying entity, to be grotesquely optimistic. With little prospect that government spending will suddenly return to pre-recession levels over the next decade or so, the ill-considered tax revenue goals of the County and the grand lease increases envisioned by the developer community appear unlikely to unfold.

Nonetheless, the now irrevocable legal commitment to office-focused development in the station area means that, whatever happens, there will be fewer riders taking Metrorail than could have been under a more balanced plan focusing on greater residential development in Reston and Tysons station areas.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Your comments are welcome and encouraged as long as they are relevant, constructive, and decent.